Investment funds were hit hard by the pandemic; their response amplified its adverse impact on financial markets and capital flows.

عربي, 中文, Español, 日本語, Português, Русский

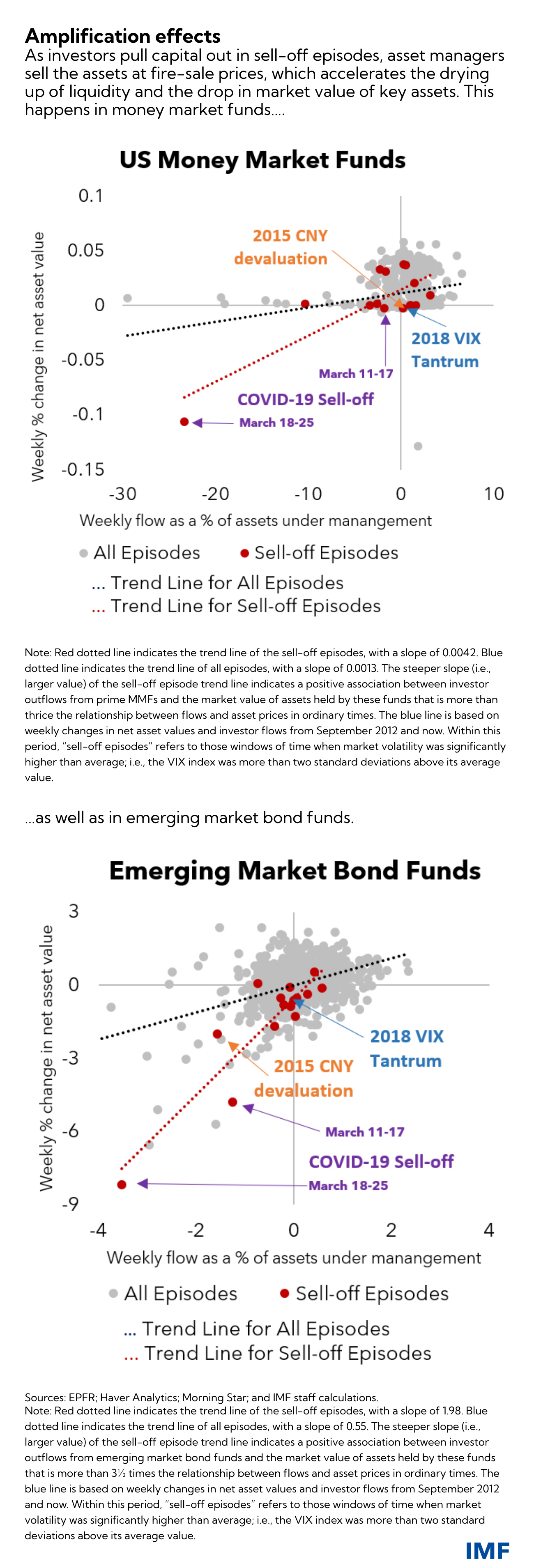

Our brush last year with one of the biggest economic shocks of our lifetimes revealed some fundamental vulnerabilities that could affect global financial stability. Caught up in the financial market turmoil generated by risk averse investors, many investment funds were heavily affected by the “dash-for-cash” that extended across borders—and which triggered significant outflows from risky assets and from emerging and developing economies. As this happened, and investor capital flowed out of money market and open-end mutual funds, asset managers were forced to fire-sell these assets, which accelerated the drying up of liquidity and the drop in market value of key assets.

Our policy recommendations would be wins for both issuers and investors alike, more than offsetting any adjustment costs borne by them.

To safeguard financial stability at the national and global levels—and better protect markets and economies from crippling capital outflows—we need to boost the resilience of investment funds. A key part of this involves reducing the scope for their business models to amplify the macrofinancial impact of adverse shocks, so their business operations are less likely to be susceptible to asset fire-sales during stress.

In a new IMF staff paper, we outline the tools policymakers can use to further strengthen risk management, especially liquidity risk management. We show how this can be achieved with a combination of liquidity management tools deployed sequentially—as needed—depending on the intensity of pressures facing a particular fund.

Vital to global growth

It’s not surprising that investment funds play a central role in global growth and financial stability. Over the past two decades, the rapid growth in the amount of capital flowing into investment funds has been a key driver of nonbank financial institutions increasing their share of global financial assets to about 50 percent. This benefits everything from entrepreneurs growing their businesses, to families buying their first home, to saving for retirement.

Investment funds are vital engines of prosperity—coming in all shapes and sizes, such as money market funds and a wide range of mutual funds. And increasingly a key feature of most investment funds is to offer daily liquidity to investors, like that offered by banks on their demand deposits. But many funds have ventured far beyond their traditional offering of large cap equity and ultra-safe government bonds to investors, into higher-risk investments such as high-yield private debt and real estate.

As these funds shifted into offering exposure to these riskier and less liquid assets to investors, their ability to make good on their promise of daily liquidity has sometimes come under pressure in the face of adverse shocks—evident during the turmoil triggered by the onset of the global COVID-19 pandemic that accelerated markedly in March 2020.

Unlike banks, investment funds generally do not benefit from public backstops, such as dedicated central bank liquidity facilities or deposit insurance. This increases the likelihood of them amplifying the adverse impact of shocks on financial markets through asset fire-sales that exacerbate illiquidity in markets and occasionally, may even generate runs.

Policies—what do we need, and how will we get there?

In this context, we identify four key objectives.

First, address incentives of investors to front-run others when adverse shocks occur. Second, decrease the existing tension between daily liquidity and exposure to illiquid assets. Third, explore options to increase structural and cyclical liquidity in some important asset markets. Fourth, decrease cross-border spillovers to emerging market and developing economies.

We then identify specific tools targeted to address these objectives.

Investors’ early-exit incentives can be best addressed by decreasing the value of selling fund shares early on. Various policy mechanisms could decrease the cost for investors of waiting to sell fund shares, thereby blunting early-exit incentives, which can precipitate sell-off episodes.

We argue that a “waterfall” of liquidity management tools is needed to reduce the risks inherent in liquidity transformation by investment funds. Under this approach, a sequence of liquidity management tools of increasing intensity can be deployed in combination depending on the level of stress or shock. For money market funds, for example, increasing liquidity buffers and making them countercyclical (the first line of defense) could be sequentially combined with locking in a proportion of investors’ shares for a minimum period of time and offering to redeem investor withdrawals in securities held by the fund instead of in-cash.

To strengthen market liquidity, policies should encourage alternative trading arrangements, such as ensuring all market participants are able to trade with each other (“all-to-all trading”). Larger and more robust liquidity backstops should also be explored—here, market-based solutions, such as dealer pre-commitments to make markets, should be the first line of defense.

Policy reform through these various measures would go a long way in limiting the need for central bank emergency liquidity support to extremely unlikely (“tail”) events. Moreover, with careful calibration, the reforms would limit moral hazard while recognizing that public liquidity backstops may be required on rare occasions given the macrocritical role of this sector.

By strengthening the resilience of these investment funds to shocks, these policies would benefit emerging market and developing countries, which our estimates suggest received 75 percent of their capital inflows following the Global Financial Crisis through these funds. When combined with appropriate domestic macroeconomic and macroprudential policies in these countries, policy action strengthening investment funds can lessen cross-border contagion, which is increasingly a risk to financial stability in emerging market and developing economies

By helping reduce the risk of market turmoil and financial instability, our policy recommendations would be wins for both issuers and investors alike, more than offsetting any adjustment costs borne by them.

International cooperation remains crucial

Our analysis underscores the importance of the ongoing Financial Stability Board-led process of identifying policy options, involving national supervisory authorities and central banks and the International Organization of Securities Commissions. The global nature of the investment fund business and fungibility of financial flows means consistent global policies precluding regulatory arbitrage are needed to secure financial stability. Policymakers worked together to make banks safer following the global financial crisis over a decade ago—now we must do the same for investment funds.